Concurrent Programming and Trio

Concurrent programming is unintuitive and hard, but quite important. People do PhDs, spend careers and win Turing awards researching on concurrent programming and distributed computing. Yet, most programmers never have to deal with it. Super consciously anyway. Node.js is all about async programming. Why is that? Because most of the hard work has been done for us by the libraries and programs we use.

Even Google agrees that concurrent programming is hard!

Why is concurrency relevant? Let’s say we’re writing a simple web app i.e. it communicates to the world using http protocol. Our app has to serve multiple requests at the same time. Our app’s backend, in turn, makes multiple database queries at the same time. We’re likely using a web framework, say Django, to write our app and host it behind a web server, say Nginx. Django and Nginx abstract out all these concurrencies for us and databases themselves are designed to handle concurrencies. We, therefore, end up writing a sequential code.

What if we’re now asked to write our app in a completely new protocol?In my case, this protocol is DICOM. Unlike http, maybe our protocol is asynchronous by definition – say WebSocket. We can’t rely on our favorite web framework and its abstractions to make our life simpler. We have to deal with the complexity of concurrent programming ourselves. Add to that additional issues that raw threading, reference counting, and error propagation bring. Not the best place to be in.

Trio and Nursery

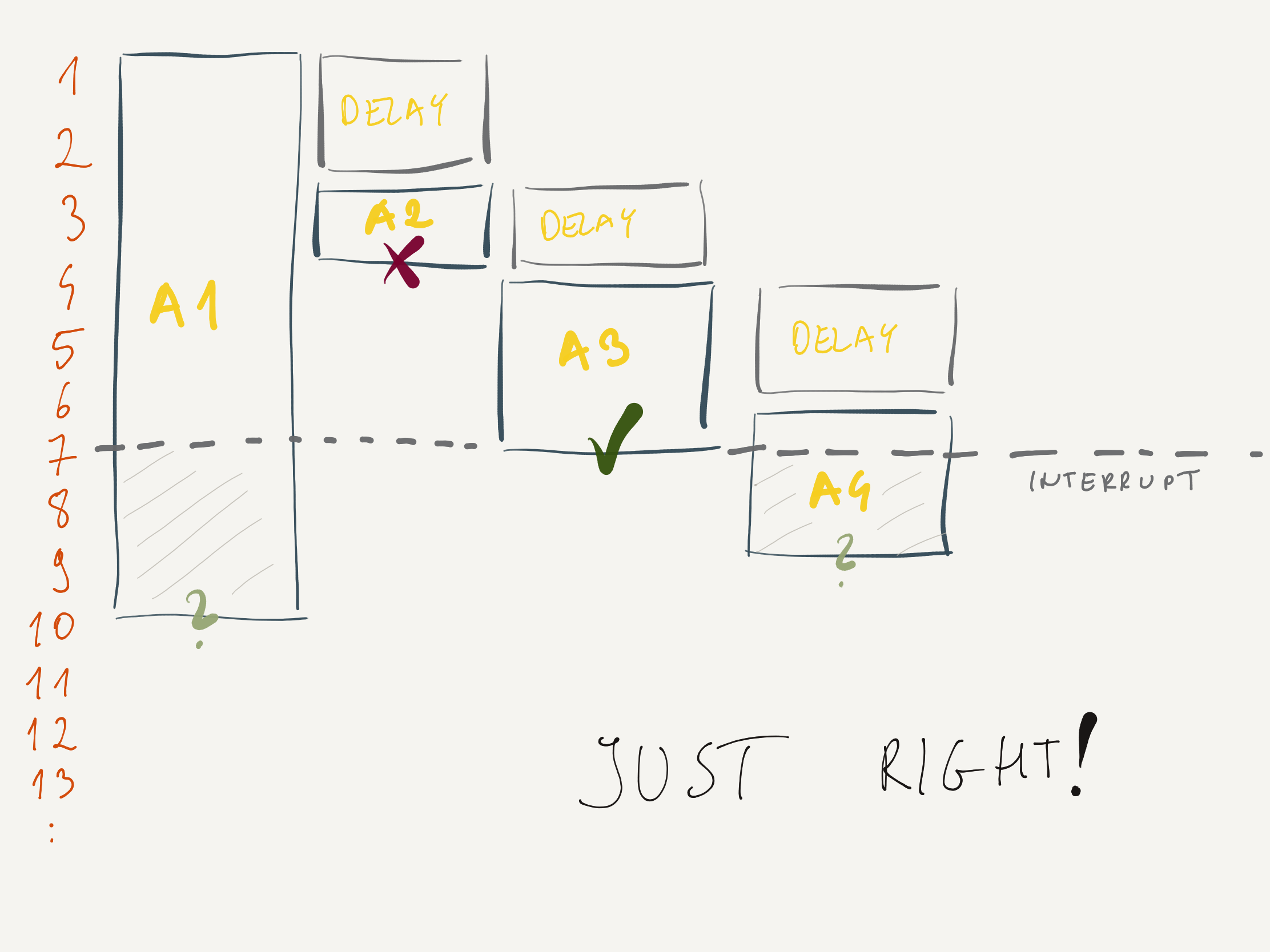

There are a lot of libraries out there to make concurrent programming ‘easy’. There are a lot of models – threads, tasks, callbacks and so on. As shown in this beautiful article by Nathaniel, they all boil down to the unintuitive goto statement that Dijkstra so vehemently opposed. In the same post, Nathaniel proposed an alternative to these models, nursery and a library called trio which implements it.

Nursery illustrated. Observe the with statement that destroys the nursery after completing the tasks async. Arrows represent the control flow. Source

In this post, I show how to implement

Code for this tutorial is available here a simple TCP protocol server using these concepts and illustrate trio library. I intentionally pick the protocols from twisted’s tutorial here to illustrate the differences with twisted, another popular async python library. Start with installing trio:

$ pip install -U trio

Let’s write a very simple program which sleeps asynchronously to see how nursery works in trio

Code snippet taken directly from trio’s tutorial:

# tasks_intro.py

import trio

async def child1():

print(" child1: started! sleeping now...")

# do not forget the await!

await trio.sleep(2)

print(" child1: exiting!")

async def child2():

print(" child2: started! sleeping now...")

await trio.sleep(5)

print(" child2: exiting!")

async def parent():

print("parent: started!")

async with trio.open_nursery() as nursery:

print("parent: spawning child1...")

nursery.start_soon(child1)

print("parent: spawning child2...")

nursery.start_soon(child2)

print("parent: waiting for children to finish...")

# -- we exit the nursery block here --

print("parent: all done!")

trio.run(parent)

What this does should be fairly obvious: parent is running child1 and child2 asynchronously. Let’s run this:

$ python tasks_intro.py

parent: started!

parent: spawning child1...

parent: spawning child2...

parent: waiting for children to finish...

child2: started! sleeping now...

child1: started! sleeping now...

[... 2 second passes ...]

child1: exiting!

[... 3 second passes ...]

child2: exiting!

parent: all done!

Note how the parent waits for all of its children to finish before exiting the nursery.

Simple Echo Server

Let’s write a very simple echo server: receive a message and write the same message back to the TCP stream.

# echo_server.py

import trio

async def echo_server(server_stream):

print("echo_server: started")

async for data in server_stream:

print("echo_server: received data {!r}".format(data))

await server_stream.send_all(data)

print("echo_server: connection closed")

async def main():

await trio.serve_tcp(echo_server, port=12345)

trio.run(main)

trio.serve_tcp creates a nursery internally and listens to TCP connections indefinitely on the specified port and forwards them to the echo_server function. Run the server using

$ python echo_server.py

Use telnet in another terminal to talk to the server. Type ‘hello’ or ‘hi’, press enter and we should see that server responds with ‘hello’ or ‘hi’.

$ telnet localhost 12345

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to localhost.

Escape character is '^]'.

hello

hello

hi

hi

^]

telnet> Connection closed.

And the log of our server should look like:

echo_server: started

echo_server: received data b'hello\r\n'

echo_server: received data b'hi\r\n'

echo_server: connection closed

We can try spinning up multiple telnet clients and verify that our server handles multiple requests at the same time.

Chat Server

That was very simple. Let’s write a more complicated protocol – a chat server like IRC. Our server should allow a user to login with a name and all the logged in users should be able to participate in a group chat.

# chat_server.py

class ChatServer:

def __init__(self):

# place to store list of current users

# this is why we used a class instead of a function

self.users = {}

async def server(self, server_stream):

await server_stream.send_all(b"<meta>: Please enter username: ")

current_user_name = None

async for data in server_stream:

if server_stream not in self.users.values():

# handle login

proposed_user_name = data.decode().strip()

if proposed_user_name in self.users.keys():

await server_stream.send_all(

b"<meta>: Username taken. Please enter another: "

)

else:

current_user_name = proposed_user_name

self.users[current_user_name] = server_stream

for user_name, user_stream in self.users.items():

if user_name == current_user_name:

await user_stream.send_all(

f"<meta>: Welcome {current_user_name}.\n".encode()

)

else:

await user_stream.send_all(

f"<meta>: {current_user_name} joined.\n".encode()

)

else:

# broadcast the data to other users

for user_name, user_stream in self.users.items():

if user_name != current_user_name:

await user_stream.send_all(

f"<{current_user_name}> : ".encode() + data

)

try:

del self.users[current_user_name]

for user_name, user_stream in self.users.items():

await user_stream.send_all(

f"<meta>: {current_user_name} left\n".encode()

)

except KeyError:

pass

async def main():

await trio.serve_tcp(ChatServer().server, port=12345)

trio.run(main)

Run it using python chat_server.py and open two telnet clients using telnet localhost 12345 in separate terminals. This is how our chat can look like:

telnet localhost 12345

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to localhost.

Escape character is '^]'.

<meta>: Please enter username: alice

<meta>: Welcome alice.

<meta>: bob joined the chat.

hi bob

<bob> : hi alice, how are you

I'm doing great thanks

<bob> : bye, I gotta go

<meta>: bob left

That was not so hard! Writing this code was also easier because error messages show the actual stacktrace. You can contrast this code with the implementation in twisted. Note how our code doesn’t involve the callback model twisted uses and reads like a sequential code. Thanks to the nurseries, our code is simpler and didn’t have to use ‘magical’ classes like the twisted version.

Conclusion

The difference made by this simplicity is tangible. Consider RFC 8305 “Happy Eyeballs” that humbly wanted to do parallel connections but with a cascading delay between them (see the below pic). Looks simple right? If we use twisted or its spiritual successor asyncio, we have to write around hard to understand 600 lines of code while trio’s version is less than 40 lines [1, 2].

Happy Eyeballs algorithm. Source: Softwaremill

Elimination of GOTO resulted in a loss of a superpower for the programmers. But then not all programmers are superheroes. Removing GOTO made programming accessible to puny humans like myself. Likewise, nurseries limit us by forcing us to do structured concurrent programming but makes it whole lot easier.