Intermediate Representations for GPUs: LLVM Does Not Cut it

Compilers are like dragons, and wrapping my head around their complexity has been challenging. Adding to the challenge, I’ve chosen a particularly tough topic within this complexity: AI compilers. What sets AI apart are GPUs and matrix multiplication kernels. In this post, I will talk about compilers for GPUs and will leave matrix multiplication kernels to another post. We will examine LLVM compiler framework for CPUs and contrast it with for GPUs. We’ll show that LLVM is not a reasonable IR for GPU programming.

How LLVM works

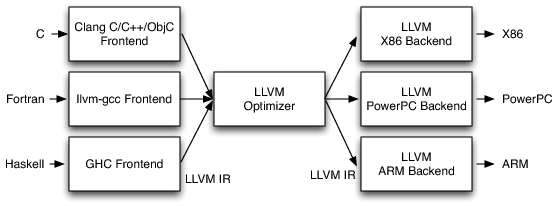

A good review of architecture of LLVM can be found in the book The Architecture of Open Source Applications. I reproduce a key diagram from the LLVM chapter below for reference:

LLVM Architecture. Source

The original design of LLVM allowed any programming language implementation to translate code into target independent LLVM intermediate representation (IR). LLVM library handed optimizations and generating assembly code for the target architecture. In other words, the backend is automated by the LLVM library, assuming you adhere to the IR contract. This design does work for CPUs – architectures such as x86, ARM and PowerPC and what not are well supported. Programming language implementors need not worry about the details of device architecture. They can restrict their attention to what is called as frontend.

To examine this design, let’s take the following vector add program:

// vector-add.c

void vector_add(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n){

int i;

for (i = 0; i < n; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

I wrote a small driver that initializes a[i] = i, b[i] = 2 * i, n = 10 and computes sum of elements of c. Let’s first compile vector-add.c to LLVM IR and then link it to the driver.

# on my x86 machine

# frontend compiles to llvm

$ clang -S -emit-llvm vector-add.c

# remove any metadata about target

$ sed -i '/target/d' vector-add.ll

# backend

$ clang driver.c vector-add.ll

warning: overriding the module target triple with x86_64-pc-linux-gnu [-Woverride-module]

1 warning generated.

# final binary

$ ./a.out

sum of element of C is: 135.000000

To verify the frontend’s independence from backend, I remove any metadata about the target device in vector-add.ll and then transfer it to my mac. My mac uses M2 chip which is an Arm based architecture. On my mac:

# On my mac (i.e arm machine)

$ clang driver.c vector-add.ll

warning: overriding the module target triple with arm64-apple-macosx13.0.0 [-Woverride-module]

1 warning generated.

$ ./a.out

sum of element of C is: 135.000000

Thus, LLVM IR generated for x86 works almost seamlessly on arm64. This is the super power of a well designed intermediate representation.

LLVM doesn’t cut it for GPUs

The title of this section might be controversial, but I will explain why. The above design, unfortunately, doesn’t work for GPUs.

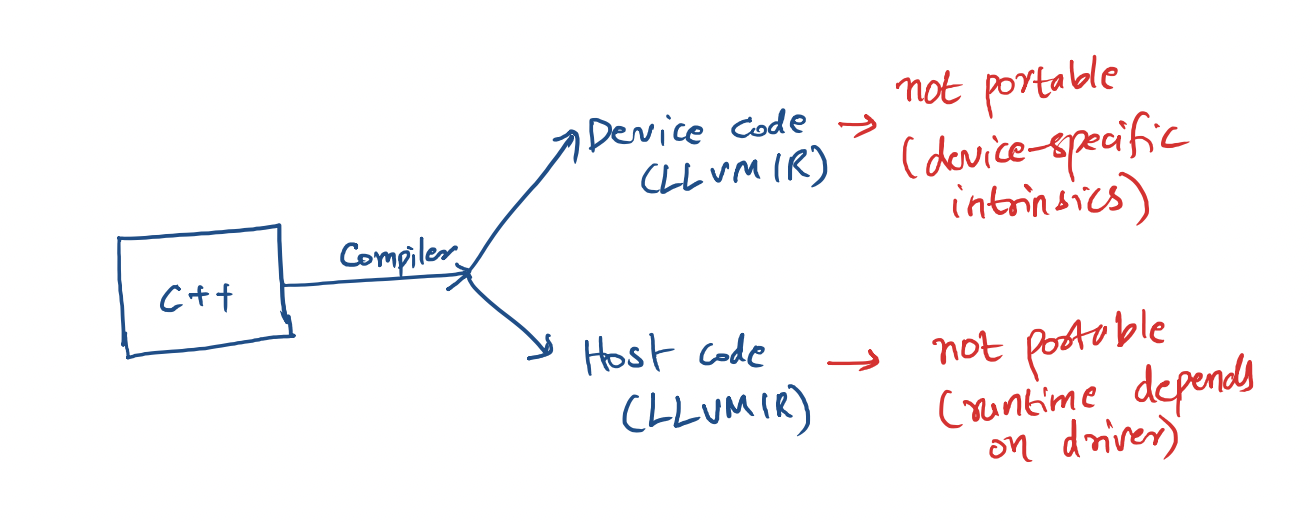

I’m not saying that such a model cannot be implemented for GPUs. Instead, what I mean is that LLVM doesn’t actually implement it for GPUs. This is because LLVM relies on intrinsics that are specific to each architecture. It has become the job of a frontend to use the right intrinsics and conventions for your target GPU. Besides, runtimes are also not abstracted and you need to use device specific driver APIs to execute compiled GPU code. Therefore, generating vanilla LLVM IR doesn’t provide a backend for all GPUs as seamlessly as it does for CPUs.

Summary why LLVM doesn’t cut it for GPUs

To examine this, we’ll write a simple vector-add program in SYCL and compile it with AdaptiveCPP, which is a compiler based on LLVM that works for all GPUs. I have shown how to set it up for different architectures in a previous post. To recap, a single source code written in SYCL can compile to all GPUs if we use AdaptiveCPP. Here’s a simple vector-add program written in SYCL.

// vector-add.cpp

#include <sycl/sycl.hpp>

using namespace sycl;

void vector_add(float* A, float *B, float *C, int n){

// Create buffers for A, B, and C

buffer<float> bufA(A, n);

buffer<float> bufB(B, n);

buffer<float> bufC(C, n);

// Create a SYCL queue to submit work to

queue q;

// Submit a command group to the queue

q.submit([&](handler& h) {

// Create accessors for buffers

auto accA = bufA.get_access<access::mode::read>(h);

auto accB = bufB.get_access<access::mode::read>(h);

auto accC = bufC.get_access<access::mode::write>(h);

// Define the kernel

h.parallel_for(range<1>(n), [=](id<1> i) {

accC[i] = accA[i] + accB[i];

});

});

// Ensure all work is completed

q.wait();

}

On my Nvidia GPU, I compile this using the following command:

$ acpp vector-add.cpp driver.c --acpp-targets="cuda:sm_75" -O2

$ ./a.out

sum of element of C is: 135.000000

That’s reassuring: we got the same result on GPU! Now let’s emit LLVM to examine the IR:

$ acpp vector-add.cpp --acpp-targets="cuda:sm_75" -O2 -S -emit-llvm

$ llvm-dis-16 vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.bc

$ file vector-add*

vector-add.cpp: C source, ASCII text

vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.bc: LLVM IR bitcode

vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.ll: ASCII text, with very long lines (343)

vector-add.ll: ASCII text, with very long lines (639)

*.ll files are the LLVM textual representation of our program. Let’s examine number of lines.

$ wc -l vector-add*.ll

110 vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.ll

32926 vector-add.ll

33036 total

Device Code

Let’s first examine the smaller file vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.ll. From the name, you can guess that this is a kernel – in other words, it is the GPU device code. We can confirm this by reading the target triple at the top of the file.

$ head -n 5 vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.ll

; ModuleID = 'vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.bc'

source_filename = "vector-add.cpp"

target datalayout = "e-i64:64-i128:128-v16:16-v32:32-n16:32:64"

target triple = "nvptx64-nvidia-cuda"

ptx serves a role similar to assembly for Nvidia GPUs. It’s more complicated than that, which we’ll discuss in a later post. Let’s observe ptx specific intrinsics:

$ grep 'ptx' vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.ll

; ModuleID = 'vector-add-cuda-nvptx64-nvidia-cuda-sm_75.bc'

target triple = "nvptx64-nvidia-cuda"

%5 = tail call i32 @llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.ctaid.x()

%6 = tail call i32 @llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.ntid.x()

%8 = tail call i32 @llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.tid.x()

declare i32 @llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.ctaid.x() #2

declare i32 @llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.ntid.x() #2

declare i32 @llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.tid.x() #2

attributes #0 = { mustprogress nofree norecurse nosync nounwind willreturn memory(none) "frame-pointer"="all" "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="sm_75" "target-features"="+ptx78,+sm_75" }

attributes #1 = { mustprogress nofree norecurse nosync nounwind willreturn memory(readwrite, inaccessiblemem: none) "frame-pointer"="all" "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="sm_75" "target-features"="+ptx78,+sm_75" }

Here, you can see intrinsics like llvm.nvvm.read.ptx.sreg.ctaid.x(). These are used as though new LLVM instructions were created just for Nvidia. Thus, this code can’t be run on any other GPU.

Runtime

Let’s now examine vector-add.ll. This file has 32926 lines! For reference, vector-add.c compiled on CPU contained just 64 lines. Why do we have thirty thousand lines in vector-add.ll? To make things even more confusing, this file is being compiled to CPU (host in GPU lingo). This can be confirmed by examining the target triple:

$ head -n 5 vector-add.ll

; ModuleID = 'vector-add.cpp'

source_filename = "vector-add.cpp"

target datalayout = "e-m:e-p270:32:32-p271:32:32-p272:64:64-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128"

target triple = "x86_64-pc-linux-gnu"

You might wonder why we need a CPU part of the code when we’re compiling for GPU. Recall that GPU still needs to be controlled by CPU and GPU can’t do many things such as I/O. In fact CPU needs to do a lot of work:

- Data transfer (via PCIe interface usually) from CPU to GPU

- Add kernel code (see above) to asynchronous queue

- Wait for the results to be ready on GPU

- Transfer the data from GPU to CPU

Code to execute all these tasks are usually written in the driver. In the case of CPU, this is generally called as runtime! Here’s an excerpt about runtime from the venerable Dragon Book:

The compiler must cooperate with the operating system and other systems software to support these abstractions on the target machine. To do so, the compiler creates and manages a run-time environment in which it assumes its target programs are being executed. This environment deals with a variety of issues such as the layout and allocation of storage locations for the objects named in the source program, the mechanisms used by the target program to access variables, the linkages between procedures, the mechanisms for passing parameters, and the interfaces to the operating system, input/output devices, and other programs.

For an introduction to how runtime works, take a look at my earlier blog post on adding a stack to a scheme compiler.

LLVM conveniently abstracts all these aspects for us when compiling for CPUs.For GPUs, however, we must interact with drivers to accomplish the above. In the case of Nvidia GPUs, the drivers are not even open source. SYCL abstracts the runtime in C++ but the compiled IR is not device independent. We can verify that vector-add.ll is not portable by observing cuda queues and other driver functions in the IR:

$ grep 'cuda' vector-add.ll --color=always | head

$_ZN7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEED2Ev = comdat any

$_ZN7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEED0Ev = comdat any

$_ZNK7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEE17get_backend_scoreES3_ = comdat any

$_ZNK7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEE15get_kernel_typeEv = comdat any

$_ZN7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEE10set_paramsEPv = comdat any

$_ZN7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEE6invokeEPNS2_8dag_nodeERKNS0_20kernel_configurationE = comdat any

$_ZNSt17_Function_handlerIFvPN7hipsycl2rt8dag_nodeEEZNS0_4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS1_10backend_idE0ENS1_10cuda_queueEEC1EvEUlS3_E_E9_M_invokeERKSt9_Any_dataOS3_ = comdat any

$_ZNSt17_Function_handlerIFvPN7hipsycl2rt8dag_nodeEEZNS0_4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS1_10backend_idE0ENS1_10cuda_queueEEC1EvEUlS3_E_E10_M_managerERSt9_Any_dataRKSC_St18_Manager_operation = comdat any

$_ZNSt6vectorISt10unique_ptrIN7hipsycl2rt23backend_kernel_launcherESt14default_deleteIS3_EEN3sbo29small_buffer_vector_allocatorIS6_Lm8ES6_EEE17_M_realloc_insertIJS0_INS1_4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS2_10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEEES4_ISG_EEEEEvN9__gnu_cxx17__normal_iteratorIPS6_SA_EEDpOT_ = comdat any

$_ZTVN7hipsycl4glue23hiplike_kernel_launcherILNS_2rt10backend_idE0ENS2_10cuda_queueEEE = comdat any

Thus, from a compiler writer’s perspective, runtime is an extra, non-portable component that LLVM doesn’t abstract away.

Conclusion

In this post, we have observed the power of LLVM IR for CPUs. The abstraction of chip architectures in the IR enabled a highly portable intermediate representation, compiling without changes for x86 and ARM64 CPUs. On GPUs, however, this portability doesn’t apply due to device-specific intrinsics and runtime code. LLVM IR, therefore, unfortunately doesn’t have the same power on GPU as it has on CPUs. Further work is required to create this portable IR.

P.S.: Attentive readers might object, saying the single-source single-compiler (SSCP) flow of AdaptiveCPP solved the issue. You picked up the plot for a later post :). Code for this post is available here