Technology is a Source of Socioeconomic Inequality

It is well accepted that new technologies and innovations drive human progress. Industrial revolution, green revolution and information revolution made human life easier than ever before and created wealth for everyone. However, inequality seems to have grown with every technological revolution. The picture of exploited London workers during the industrial revolution comes to mind. In this post, I describe one of the possible sociological mechanisms that lead to such inequalities among people as new technologies are adopted.

Industrial revolution

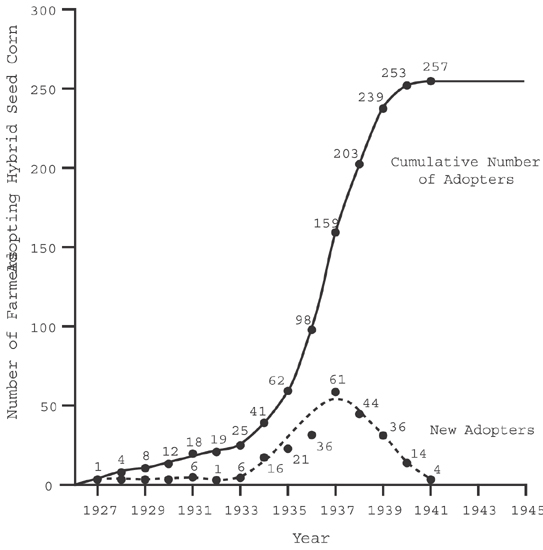

Everett’s Diffusion of Innovations provides a clear framework to think about how innovations and technologies are transferred across the populations. It uses social structure to analyze how, which and when innovations are adopted. Diffusion research has found out that the cumulative number of adopters of any innovation follows so called S-curve. Let’s take an example of agricultural innovation: hybrid seed corn adoption by a rural farming community. There’s an initial slow growth of the hybrid corn farmers until the community gains confidence, followed by hockey stick growth until there’s a saturation and the diffusion is complete. See the below figure.

S-curve of adoption of hybrid seed corn

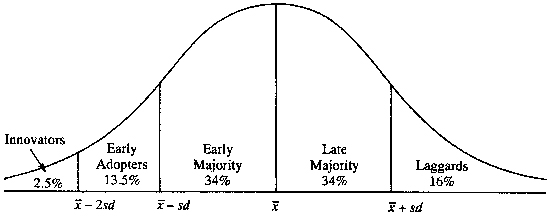

Another way of looking at an S-curve is a ‘bell curve’ of new adopters (as opposed to cumulative adopters) each year – see the dotted lines in the above figure. This bell curve allows us to segment the innovation adopters into five approximate categories based on when they adopted the innovation as shown in the below figure. One of the interesting results of diffusion research is how rich, educated and well-connected are the first to adopt any innovation. In essence, innovators are those who have higher economic, cultural and social capital in Bourdieu’s sense.

Adopter categories

Causality of this is not clear. Are innovators rich because they innovate or do they innovate because they are rich? Are laggards poor because they lag in adoption or do they lag because they are poor? You can frame arguments either way.

- Adoption of any innovation comes with a lot of uncertainty and therefore a risky process. If you’re adopting unproven technology, you have to have extra capital to account for failed innovations. If you’re poor, you cannot take the risk of trying out a potentially wasteful idea or product. Therefore, you have to be rich to innovate.

- Adopting an innovation early confers you with a significant capital advantage. Innovations often are designed to create economic benefits, save your time or create some level of comfort. Being an early adopter improves your social standing because you can disseminate its advantages to the rest of the community. Therefore, you become rich if you adopt early.

Notwithstanding this, advantages from the innovations are the most useful to the poor. Take contraceptives such as condoms for example: it is most useful to the poor since they can not afford to raise too many children. However, the first to adopt the condoms were the rich who could afford raising children.

This creates a innovation/needs paradox: Individuals or units that will be most benefited by an innovation are generally the last to adopt. People who adopt an innovation the first least need the benefits. While innovations eventually are trickled down to the needy, diffusion process widens the socio-economic gap. You can see the contours of both Adam Smith’s invisible hand theory and Karl Marx’s class analysis in this argument.

You might wonder how this is relevant to me. I can see these processes happening in front of me thanks to the raging pandemic and my job at qure.ai. Covid-19 vaccines are probably most useful to those people who cannot afford to stay put at home. Unfortunately, they are the last to accept the vaccines and overcome hesitancy. AI will make healthcare accessible and affordable to the needy and developing world but most of the conversations about it happen in the developed world.

Covid-19 Vaccines. Source

Being in a developing country makes me acutely aware of widening income inequality. Even a developed country like the US faces a deep inequality problem. It leaves me wondering if inclusive economic growth is possible. If so, what are the social and economic forces that lead to equality? These are heavy, loaded but interesting questions with wide reaching political consequences.

Anyway, my line of argument above is not new. It boils down to the relation between uncertainty and capital. Ronald Coase, in his seminal paper the nature of firm, explains how uncertainty leads to creation of firms. Schumpeter, another eminent economist and political scientist has a strong opinion on this in his capitalism, democracy and socialism. A number of other economists have put a significant thought behind this, I am sure. May be as I read these, I will have improved mental models on this problem. For now, this diffusion perspective provides me a concrete sociological model of exacerbating inequality.

References:

- Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster, 2010.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and John G. Richardson. “The forms of capital.” (1986): 241-258.

- Coase, Ronald, The Nature of the Firm. Economica, 4: 386-405.

- SSchumpeter, Joseph A . Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Harper & Brothers, 1942.